Freighter

Today would have been my dad's birthday. He died when he was just a year older than I am right now. A reminder to do the things you want to do.

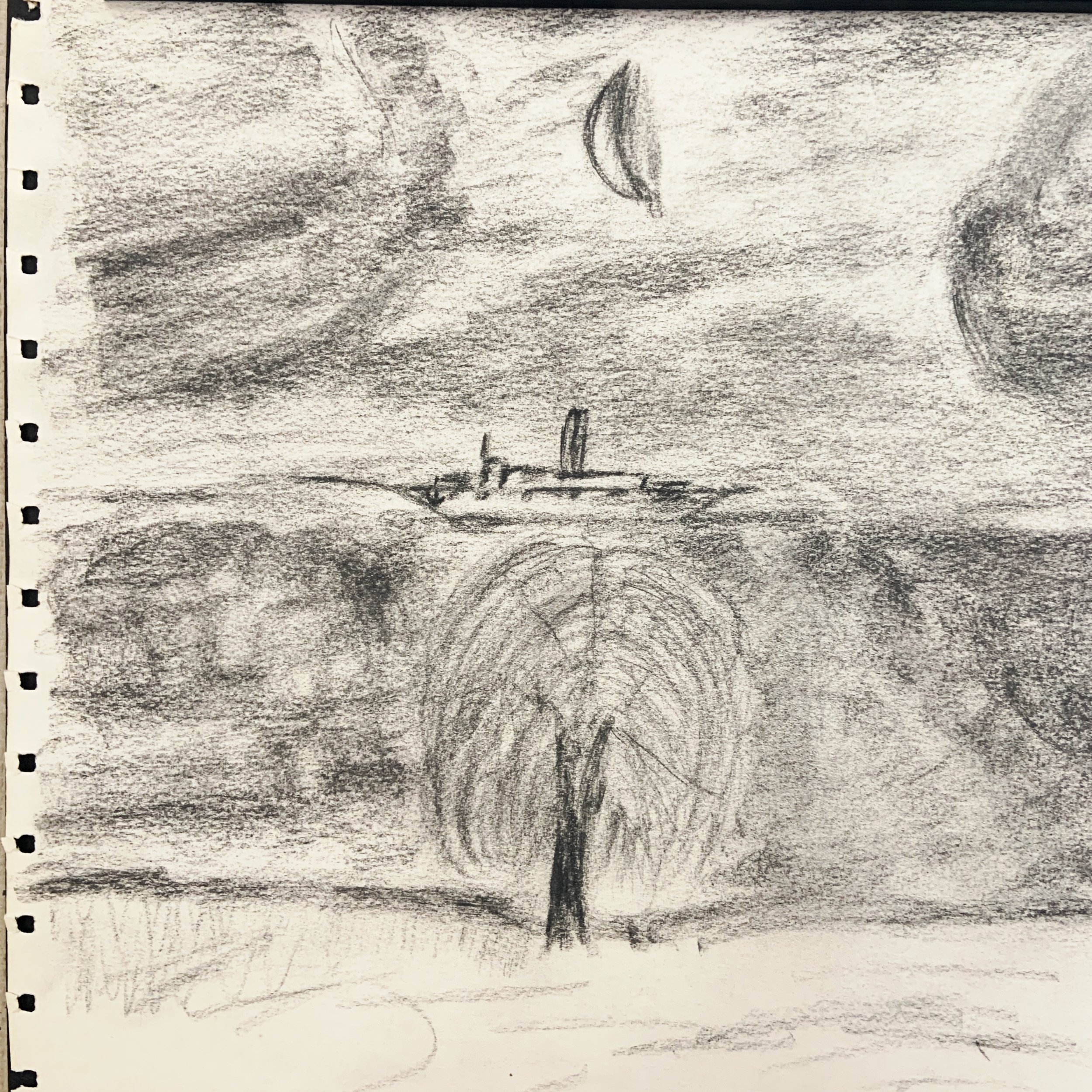

I have a charcoal drawing that he made of a freighter on the horizon at night under a half moon, low in the sky, with a weeping willow in the foreground. It’s no surprise that the subject matter is so sad and lonely.

Self-taught, he attempted many creative pursuits—drawing, oil painting, writing poetry—he even had one of those wooden boxes made for artists to keep his paints and palette in. When I was a kid he’d let me look at it occasionally and I would with wonder and amazement, taking in the nutty aroma of the bottle of linseed oil, which was slippery to the touch, rusted at the cap and leaky, causing faint stains in the box where it had a special slot. Where he got it, I don’t know.

I can’t remember him ever making a painting using the hardened tubes of color in that box but he must have at some point in his life, most of the tubes were half-squeezed or nearly empty. That box represented the promise of something about to be created, or the memory of an idea for something to be created.

He also had some sketchbooks that were filled with drawings from when he was a young man: the objects on top of his dresser; a somewhat clumsily composed horse in a stall (where would he have encountered a horse, growing up in Detroit?); my mother’s head; a bottle; a knife and cutting block with bottle cap; a leafless tree; a barn; a coffee pot; a Thunderbird. I was intrigued with the idea of the sketchbooks and felt that the drawings they contained were perfect in some way, in part, I’m sure, because it was my father who drew them.

Looking back all of these years later, I realize they were perfect because they were an attempt to reach for something bigger, something beyond, something in that void at the threshold of creation where meaning and truth exist. My father was trying to feel life at a richer level, to interpret his contained world, to keep a visual log of the things and people (and horses)—real and imagined—that were in his life.

It’s this promise of a thing yet undone, a thing yet to be created, that can keep a dreamer dreaming all her life. And, the “thing” can remain perfect in her head. All the fine details don’t have to be worked out, the problems in the design can remain unsolved. The beautiful thing can also become a burden, something sad, like a box of unused paints in the corner of the basement, hardening each year to the point of uselessness.

One of the last times I saw him we went to the Detroit Institute of Arts. I was enrolled in an art history class at a local community college and we were assigned pieces to write about that were housed at the DIA; mine was The Wedding Dance by Peter Brueghel.

Walking into the wide-open, marble-floored entrance hall lined with suits of armor, my father smiled, breathed in deeply, and put his hands in his pockets. I asked him what he was smiling about and he told me, “It’s a nice feeling here, isn’t it? You get a nice feeling being here. I feel good here.” I knew what he meant. Being in proximity to things made by men and women—just for the sake of making them, because that was the way they chose to speak in the world—was transformative. It made way for thinking of things not yet visible in ourselves.